October 24, 2023

Towards the end of the summer, I had a persistent intrusive thought: My life is lonely. I live a lonely life. We had just got back from Ireland, and I repeated this couplet silently to myself, as if to test whether it was true. I don’t think it is true, really, but I do often feel quite alone. It’s embarrassing for me to admit this, by the way - I don’t like the idea of people thinking of me as lonely, pitying me even. But the isolation doesn’t feel mine, exactly. It’s built-in, more intractable than something I can solve by simply getting out more.

I see people. We have good people here in small town America, a place that is built with the express purpose of siloing people into individual spaces, i.e. cars and single-family homes. NIMBYs block mixed use development and multi-family complexes, decrying the scourge of the high rise. Sidewalks suddenly end. Highways can’t be crossed on foot. Public transportation is non-existent, there’s nowhere to sit for free in public, more parking than amenities. Drive-thru everything. Against this larger scheme of organized isolation, I manage to see two friends for a standing Sunday morning coffee date with kids. Sometimes I make evening plans, though rarely. Does all this make me more or less lonely than the average 40 year old mom?

More than people, I see cars. I drive more than I talk out loud. I drive from here to there and back, beating the same paths, parking, paying, loading up, backing up, occasionally leaning on my horn just to say something.

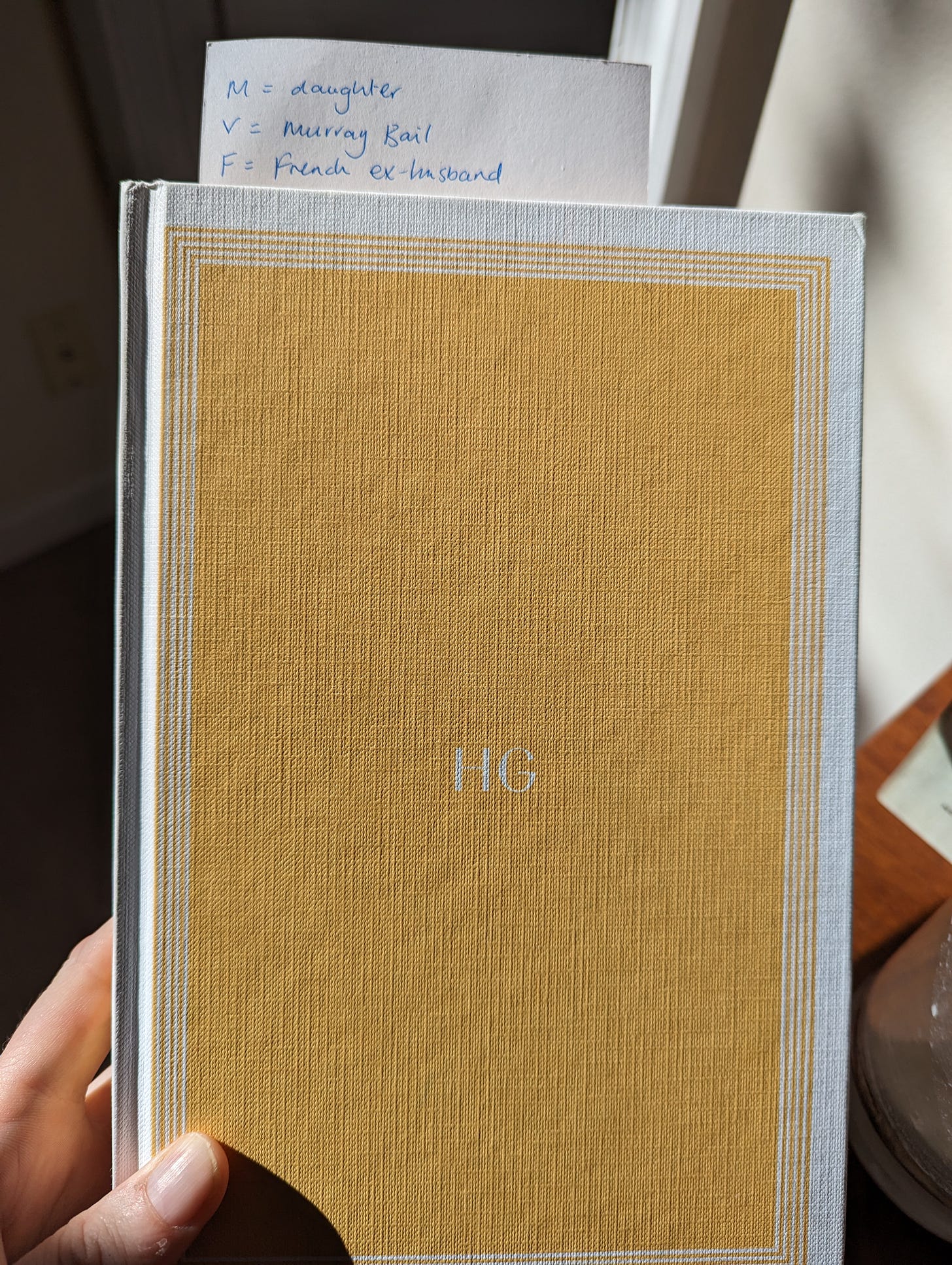

Helen Garner’s diaries are so filled with people that it can be difficult to keep them all straight, especially since she denotes people’s names with a single letter, and some recur only occasionally so that you might find it useful to keep a running list on an index card while you read, use it as a bookmark. This is what I’ve done while re-reading parts of The Yellow Notebook, the first volume of Helen Garner’s diaries that spans 1978-1987, over the last month or so.

I thought I was having a Baader-Meinhof thing about Helen Garner, her name suddenly appearing in multiple places seemingly at random, but it’s actually just that two of her books are being reissued in the U.S. and there’s coverage. It’s some well-deserved late-career fanfare for a writer who has been doing it for decades. If you haven’t heard of her: she’s an 80-year-old Australian author, probably best known for her 1977 novel Monkey Grip, and her later one, The Children’s Bach. She’s beloved in Australia, and she recently published three volumes of her diaries, beginning with The Yellow Notebook in 1978 and ending with How to End a Story in 1998. This month, Garner told the LA Times:

“My writing in my diary is the best writing that I do,” she says. “And it’s because it’s sort of free. I’m not imagining it as work. I’m doing it for that sort of pleasure of writing.” She adds that some colleagues dismissed these private writings. “They said, ‘This isn’t literature.’ But it’s about the joy of handling language. You turn yourself into a writer by making sentences.”

The diaries are episodic and disjointed, snapshots of life - there are no days or dates listed, just a collection of fragments from each year. It is clear that, for Garner, life is not days, or events, or timelines, but people.

I first heard of Helen Garner through the Australian writer Jessica Stanley’s newsletter (which is excellent), and I recently wrote to Jess for help decoding some of the cast of characters in the diaries. Because while they contain enough beauty, intrigue, insight, and wisdom to carry a reader endlessly, I am nosy, and I wanted to know who these (sometimes outrageous) people were, and what relationship they bore to the author. Thanks to Jess, who kindly emailed me back, I learned that M is Garner’s daughter, F is her French ex-husband, V is her awful husband and celebrated novelist Murray Bail. I was thrilled to discover this, and to put a face to the ‘character’ of V, a man who appears towards the end of The Yellow Notebook. He is married when she meets him, and her last diary entry of 1987 reads:

“The monolith of his marriage, and my own solitariness and flimsiness in comparison. I feel very small, slight, impermanent. It is not too late for me to save myself.”

I haven’t read the second and third volumes, but now I can’t wait to get into them. I have a whole list of letters corresponding to people I haven’t encountered yet. Maybe dwelling amongst Helen Garner’s people will make me braver in my own life, more receptive to leaving the house.

When we were in Ireland, I spent all my time around people - family, friends, strangers on the bus, people in pubs, cafes, the theater, on the beach. I was never really alone. The constant stimulation of conversation, interaction, and background noise reminded me of an earlier time in my life and though I found it tiring, I felt that I was tired in a good way, like I was learning to walk again after a convalescence.

In Charlottesville, it’s just me and Elliott a lot of the time. One day last week, after I picked him up from preschool, we went to a coffee shop downtown for a kid-temperature hot chocolate with marshmallows. The place was full with people working on laptops, one at each table with the accompanying seat hanging out empty on the other side. Elliott didn’t want to sit outside, so he marched up to the front of the cafe where the cushioned window seat was occupied by a woman in a red coat speaking on the phone. I want to sit here, he said to her, and I rushed after him to say no no, this seat is not free love, sorry, sorry about that. The woman scooted over and said, please, sit here, I would love for you to sit here. I thanked her profusely and Elliott climbed up onto a pile of cushions, while I took the outside chair. I’m the king of the coffee shop, he said, and he was.

The woman introduced herself to Elliott. She held out her hand. He shook it, and she went back to her phone conversation. After drinking half of his hot chocolate, Elliott decided it was time to go, and as we were getting up to leave, the woman paused her phone conversation again and said to Elliott, do you have any brothers or sisters? He was unusually stumped by this question, I think because it had genuinely never occurred to him to consider whether he had any brothers or sisters. No, he said, a little uncertain. Do you want a brother or sister, the woman asked, as if she were about to pull one out of her pocket. I was going to intervene and make a joke, shut down this line of questioning, but he answered firmly, no, I like being on my own. It could have ended there. I would have walked back to the car floating on clouds, but she went on: Oh but you must, you need a little sibling, being a big brother is a very important job, the most important job of all. Her theatrical tone seemed calculated, as if she knew it would drum up a feeling of want in a three year old. Elliott was not immune to it - I will be a big brother when I’m a bit older, he said.

Later, at home, I felt a futile anger that this stranger may have planted the seed of desire in my only child, a desire I would not be able to fulfill for him. But obviously it would have happened eventually regardless - he would have become aware of his only-child status and either asked for a sibling or decided he never wanted one, that his first response was true - “I like being on my own.”

My son loves people. He approaches and talks to them in public constantly, asks people at parks and playgrounds to be his friends, tells everyone he encounters his full name, age, and address. “My mom’s name is Helen,” he says, inviting me in, dragging me out of my self-imposed isolation and into the human world. He’ll be alright.

My friend Sarah told me she feels her creative life is richer when it receives “sufficient inputs” from the outside world, inputs that are nourishing, and cultural, and smart. “It can’t just be reading books,” she said. “It has to be experience and living people, too.” And I was reminded of this snippet from a New York Times interview with the writers Megan Nolan and Nicole Flattery in which hanging out with people is the work:

I turned 40 yesterday. It is not too late for me to save myself.

Yours,

Helen.