February 23, 2012 - Fort Kochi, India (28 years old)

I’m sitting in a gorgeous cafe in the heart of Fort Kochi. Hours ago, I would not have been able to summon the word gorgeous to describe this place. I arrived in the dark late last night and wandered off from my homestay in the wrong direction looking for something to eat. Finding nothing, no stores or stalls or vendors, I bought three bananas from a woman who sat by a fire on the side of the road with a huge bucket of bananas next to her. I don’t even know if she was trying to sell them. Then I went back to my homestay, ate the bananas, and slept past noon today. If I was asleep, I reasoned, I would not have to endure the day. I wanted to go home. I wanted M to get in touch to say that he still wanted me to come visit him.

There was a weak wifi signal at the homestay, so I sent M a message this morning. I’ve already checked twice to see if he has replied. Nothing. I really wanted him to reply and for his reply to be encouraging. I should have kept quiet and got on with being in India.

February 9, 2023 - Charlottesville

In September last year, I started working out at a fitness studio called Orangetheory. I won’t bore you about it, but in short, it’s an interval training class whose main gimmick is that you wear a heart rate monitor to track your effort while a coach tells you what to do. After each session, I’d receive a summary in an app of the ways in which my heart had been taxed. For all of the first month, I spent most of every workout in the ‘red’ zone, my heart pushed close to and sometimes beyond 100% of its maximum capability. I would leave the studio dripping with sweat, red-faced, sort of shell-shocked, and wake up the next day in tremendous pain. I kept showing up, three or four times a week.

Strangely, I didn’t dread working out in this fashion the same way I had, in the past, felt despair at the very thought of jogging for even one mile. I used to feel exhausted at the idea of going to a gym because I didn’t know what I should be doing in it. With Orangetheory, I just showed up and someone would tell me to run, row, or lift weights. In this way, I have been able to truly absorb and understand for the first time the very widely known fact that exercise measurably improves one’s physical and mental health. I’ll be 40 this year. Anyway, I’m embarrassed to be writing about Orangetheory—I recently heard Kate Berlant on a podcast describe something as ‘deeply déclassé’ and now I can’t stop repeating that phrase in my head whenever I’m high-fiving the coach on my way to the treadmill.

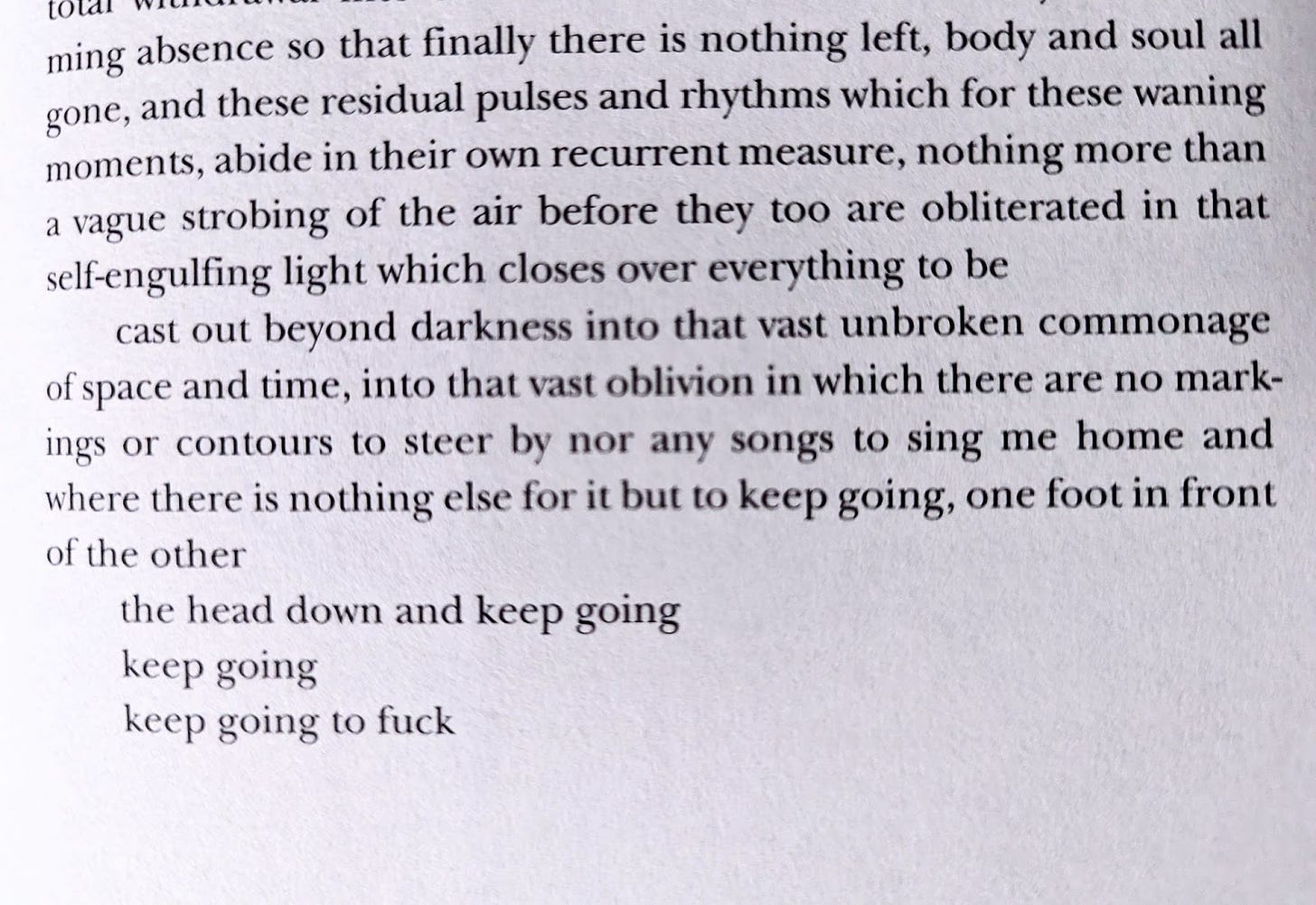

One recent Saturday, I wasn’t able to go to my usual class because it clashed with a toddler birthday party. It was worth it, Elliott loved it, and only badgered the host mom a little to hurry up and do the cake part now. But by the afternoon I had excess energy, and was feeling ill at ease, so I quickly got changed and headed out for a run, much to my family’s relief. I felt that old, familiar dread as I stepped out of the house. I set off at what felt like a plod, listening to an episode of The Daily about people crossing the Darién gap. If I hadn’t been listening to that particular episode, I doubt I would have run as far as I did, farther than I’ve ever run, until I couldn’t feel my legs, until it felt as though it might hurt more to stop than to keep going, the thudding of my feet on the pavement having become, somewhere around mile 3, meditative.

The Darién Gap is the strip of dense mountainous jungle that connects Colombia to Panama, South America to Central America. It is a wilderness often crossed by people from all across South America attempting to reach the United States, and in particular in recent years has seen an increase in the number of Venezuelans passing through. It’s an absolutely barbaric journey, a cruel test of the limit of human endurance, and many don’t make it to the other side. Blisters and injuries often mean death. Dead bodies are encountered along the way. In this particular episode of The Daily, a Venezuelan mother and her 6-year-old daughter barely made it through alive. Some months later, they had made it as far as Honduras on foot when, in a reversal of a policy loophole that would have allowed them to enter the US and seek asylum, President Biden closed the border to Venezuelans.

Once, a clickbait headline tricked me into briefly believing that pregnancy represented one of the greatest feats of human endurance, which sounds nice and empowering, but is also provably false. Heavily pregnant people cross the Darién Gap carrying children on their backs.

Sometimes we get lucky and we don’t notice that we are building endurance incrementally, simply by continuing to move. I’ve never been able to intentionally build it, too impatient and frustrated by my limitations - I had to trick myself with a gimmicky workout. In order to keep running, I had to be accompanied by a reminder that people do much harder things every single day, in life threatening conditions. More often, the mental and physical strength to keep going is summoned inside a moment during which it feels as if time has stood still, followed by another, and another.

In January, I read Getting Lost, the newly translated diary by Annie Ernaux which documents her 1989 affair with a Russian diplomat. It is 237 pages of agonizing obsession - waiting for him to call, preparing for his visits, counting the days since he last called. Though the diary is often a slog to read, I found myself continually drawn back into its repetitive intensity. I felt frustrated at the author for waiting for a man in this way, but I was also morbidly curious about just how much she would endure before it all fell apart. By the end (denoted by the fall of the Berlin Wall and her lover’s return to Moscow) she was waiting weeks for just a crumb of communication from this man and, I admit, I’d lost a little respect for her.

When I finished that, I read A Simple Passion, which is a slim memoir that Ernaux published a year or so after the end of the affair, in 1991. It is not at all a slog to read. Similarly intense, but somehow light as air, sharp and direct. The narrator, the very same person who narrated her diary—that is, the author—lays out her folly in clear, spare prose and the reader feels only admiration for her candor.

In A Simple Passion, Ernaux writes:

Naturally I feel no shame in writing these things because of the time which separates the moment when they are written—when only I can see them—from the moment when they will be read by other people, a moment which I feel will never come. By then I could have had an accident or died; a war or a revolution could have broken out.

When I came across my diary entry from February 2012, I felt frustrated at the author. I lost a little respect for her.

Since I wrote this diary entry, many wars and revolutions have broken out. The world is completely different. The person who wrote this is a stranger to me. The person she is whining about was not at all worth obsessing over in this way. We’d met on an earlier leg of the same trip and then gone our separate ways; he went back home to his job, and I traveled onward to India where I spent the first weeks of my visit daydreaming about landing in his snowy city. I suppose I was lonely. I became lethargic and despondent, unadventurous and obsessive about finding internet access.

I stopped writing in my diary after this entry. I admit that I gasped when I came to the end of it, turned the page, and saw that I had written nothing more in the notebook at all. And though I remember the rest of the trip around India very well—I snapped out of my torpor soon enough, made some new travel friends, and later met my Dad in Delhi to begin two weeks traveling together around Rajasthan—I think of that time as partially lost, now, because there is no written record.

I didn’t write in a diary again after that for more than a year. The written record starts back up again in March 2013, in a completely different life. There are other diary-gaps like this in my life, blank months and sometimes years that I struggle not to think of as lost.

The evenings are getting brighter, and there have been some days in the high 60s here. This fall and winter were short, shorter than usual, getting shorter every year. Mama, is it the summer? Elliott asked one 68 degree January day. No! No, I said. It’s still winter. It just feels like summer because it’s warm, but it shouldn’t be this warm. Why? he asked, reflexively, as I should have known he would, and I didn’t know where to begin to explain. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about how to explain climate catastrophe to my son, and am no closer to figuring it out.

Since moving to the US, I experience seasonal affective disorder in reverse: I dread the relentless summer. Every year, I look at the months between May and October as time to be endured. Life is paused! I will resume living when I can wear boots again! But the summer gets longer every year, and my alive-window shrinks, so it’s time now (nine years in) for me to figure out a way of living with the summer. Elliott changes drastically every six months, I don’t have time to throw away. How do I transform my outlook on this? How do I quash this habit of wishing away, after having wished away my whole life so far?

Yours,

Helen.